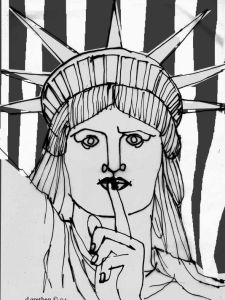

Gawker, the Freedom of Expression, and the Power of Consequences

Is Gawker violating its writers’ rights if its chief executive editor de-publishes a controversial post?

What about if a company’s CEO is forced to step down in the face of a threatened boycott over the CEO’s political positions? Is an artist being “censored” if a comic book publisher cancels his covers and suspends him? Is it an unconstitutional “ban” on speech if Amazon and Walmart remove Confederate flag memorabilia from their offerings?

Across the web confusion abounds about what freedom of expression really means.

Most recently, in the messy wake of its sex-shaming post about a private citizen’s violation of Gawker’s neo-Victorian strictures on monogamy, founder and CEO Nick Denton (who pulled the post) had this to say to his editors:

What I can’t accept is an unlimited and subjective version of editorial freedom. It is not whatever an editor thinks it is; it is not a license to write anything; it is a privilege, protected by the constitution, and carrying with it responsibilities.

Literally, every part of that last bit is wrong.

The editorial autonomy of Gawker writers is not constitutional in nature. It is a license granted by their employer—i.e. Denton. Absent a binding contract, it can be revoked at any time without running afoul of anyone’s rights, and certainly not running afoul of anyone’s constitutional rights.

The constitutionally protected freedom that Gawker writers do have (as do we all) is not to publish at Gawker. The Constitution restricts the power of Congress, not the discretion of Nick Denton.

Nor is that constitutionally protected freedom a “privilege.” It is a right.

And it does not have to be exercised responsibly.

It vexes me when people who should know better get sloppy in their framing. Messy language leads to messy thinking and, in the process, dilutes effective defense of this crucial freedom.

Perhaps a libertarian(ish) review is in order.

“FREE SPEECH” V. FREEDOM OF SPEECH

Although routinely used in Supreme Court decisions, the words “free speech” do not appear in the Constitution. In my opinion, overuse of this terminology induces people to mistakenly believe their speech should always be costless and consequence-free.

That is not how it works.

Speech requires a forum, which must be paid for by someone.

In public forums paid for by taxpayers, “time, place and manner” restrictions may be imposed to keep things orderly. But content-based discrimination is not permitted. Even the Nazis get to express themselves.

In private forums, on the other hand, the property owner gets to decide what speech he is willing to host.

There is no “free speech” right to interrupt a Muslim prayer service at the National Cathedral. The Cathedral’s owner, which is the Episcopal Church, gets to decide what sort of speech occurs there. It doesn’t have to (but may if it wants) host Muslim-haters, atheists, rude people, or morons.

Similarly, bookstores are not required to carry every book printed just because the author claims a “free speech” right. The corner market does not have to sell every conceivable magazine. Art galleries do not have to make room for every painting. Radio stations do not have to play every song.

And Gawker does not have to publish every post. (I would totally make it publish this one.)

If a speaker wants his speech to be “free” in the sense of not having to pay for the forum, he must either utilize a public forum or find a private owner willing to host the content gratis. Luckily, in this day and age, there are lots of options for that.

Gawker is not one of them.

Like other private publishers and forum owners, it exercises its right to decline hosting or publishing content it dislikes. There’s a term for that right.

…Oh yeah. Freedom of speech.

FORCE VERSUS CONSEQUENCE

It is tempting to say that Brendan Eich was “forced” to resign from Mozilla over his position on same-sex marriage. That Richard Albuquerque was “forced” to pull his Batgirl cover variant. That TLC was “forced” to cancel the Duggars.

That Nick Denton was “forced” to pull the now infamous Gawker post.

It sounds more melodramatic and provocative to phrase it that way. But to the extent it’s semantically correct, this is not the kind of “force” that runs afoul of the freedom of expression.

Wrongful force is actual physical force used to prevent or punish speech or other forms of expression.

This includes all governmental interference, because government action by definition involves force. Even civil regulations (like fines) eventually end with puppy-killing SWAT teams. Of course force exercised by private actors, in the form of violent reprisals, also suppresses freedom and therefore should be resisted with the same passion.

Preventing forceful suppression of expression is a higher order principle. When triggered, that principle transcends issues about the content of the speech being defended.

Why?

Because speech is the most powerful weapon that ever has or ever will exist.

It has the power to topple kings, eviscerate falsehoods, destroy paradigms, provoke thought, change minds and hearts, alter the course of history, and transform the world.

And it can do all that without shedding a drop of blood.

A weapon like that cannot be entrusted to the exclusive control of the few. Enlightened rulers using force to curtail speech have too often gotten it wrong. Power once ceded can rarely be retrieved, and battles not fought with words and ideas will be fought instead with violence and bloodshed.

We cannot retain the best of speech without protecting its worst. We cannot extract its power to do harm without diluting its power to do good.

EVERYTHING BUT FORCE IS FAIR GAME

That being said, everything short of physical force is fair game.

A Congressional communications director can be pressured into resigning (or fired) for making snarky comments about the President’s daughters. TLC and A&E can cancel their reality television lineup for any reason consistent with the contracts negotiated. Customers can boycott wedding photographers or bakers in retaliation for expression of disfavored opinions. Landlords can refuse to rent to people with Confederate flags in their rear windows. Employers can bypass applicants over their social media postings.

Firing. Boycotting. Refusing to hire. Pulling advertising. Cancelling subscriptions. Social media flame wars. De-publishing. Disassociating. Shaming.

All of these are fair game. All of these are themselves protected acts of expression.

They may make life unpleasant for the target. They may feel coercive or even deeply wounding.

They’re supposed to.

If speech didn’t have that power, we wouldn’t bother protecting it.

Deciding to refrain from speaking because such consequences are too unpleasant is not a response to force. It is a response to speech.

GAWKER IS GETTING SPOKEN TO, NOT SUPPRESSED

If Gawker were being threatened with forceful suppression of its speech, defending against that violation would be a higher order principle that transcended all others. Personal feelings about the content of the speech would be secondary.

But where no force is imposed or threatened, those secondary principles are the only ones at play. The whole point of the higher principle is to create a circle of freedom in which ideas, without limitation, can be explored and judged on the merits. If we never got around to the judging part, we would destroy the very reason for preserving the freedom.

Nothing happening at or to Gawker (in this specific case) poses any threat to anyone’s fundamental right to free expression. The writers are free to write. The owners of Gawker are free to choose what to publish. The editors are free to “fall on their poisoned pens” in protest. Advertisers are free to abstain. Readers are free to boycott.

None of this constitutes a violation of anyone’s freedom. It’s what freedom looks like.